Hanging Fire (Suspected Arson) by Cornelia Parker

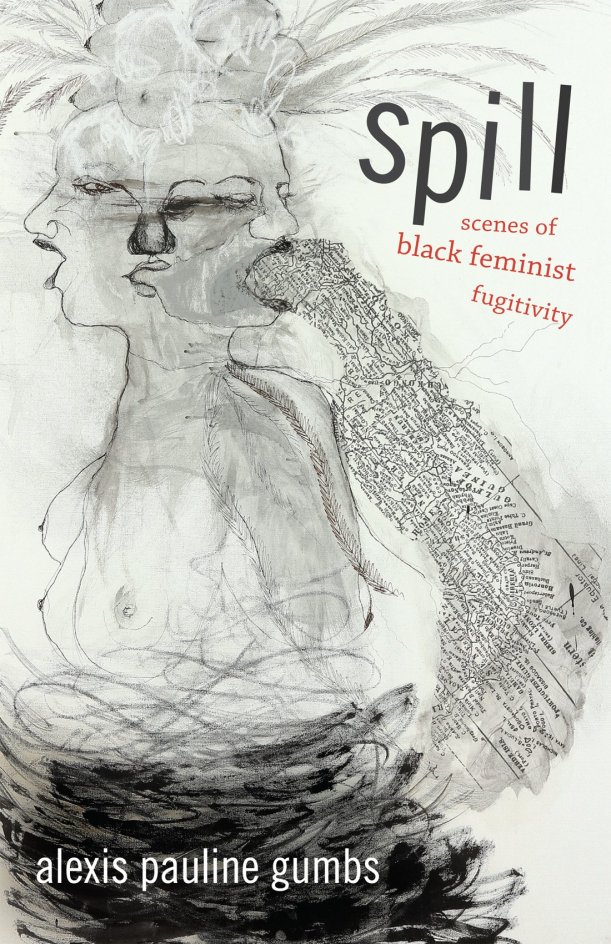

When I opened Alexis Pauline Gumbs’ Spill for the first time, I was immediately reminded of a book I read last semester by the same publisher: In the Wake by Christina Sharpe, which uses the wake of a slave ship as a metaphor for contemporary black life. Sharpe frames her whole metaphor around the varying definitions of wake, including the actual wake of a ship, being awake, the wake as a vigil, and more. In a very similar way, Spill is structured around different definitions of the word spill, in addition to being an homage to Hortense Spillers, one of Gumbs’ black feminist heroes, a theorist, and a literary critic. This structure serves several purposes, but there was one that stood out in both In the Wake and Spill. In both books, the authors speak about black American experience, struggle, resistance, and strength from slavery to present day, although Spill zeroes in on black female experience. By centering their works around vastly different definitions of the same word, Sharpe and Gumbs remind us that there is no singular black (female) experience despite an age long history of societies, structures, and messages insisting the opposite.

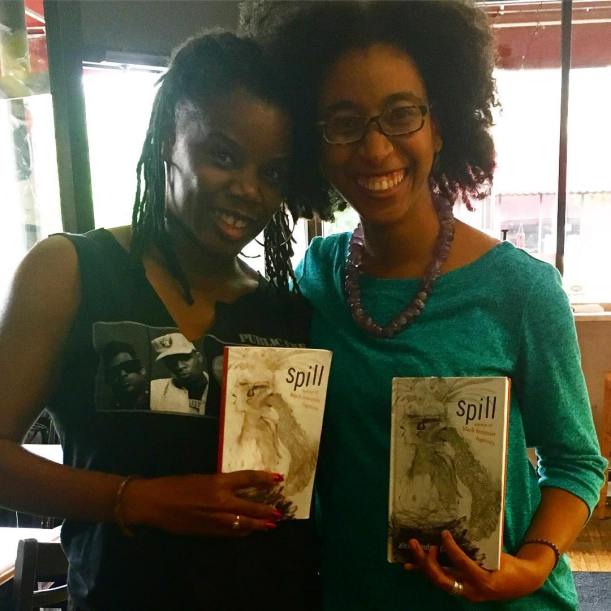

In a similar vein, both books serve the very important role of complicating the narrative of the black freedom struggle by adding stories of extreme, powerful resistance in the face of a country, society, and history that is designed to crush. Gumbs does this particularly powerfully, specifically in the chapter ”How She Survived until Then”, framing black female survival as a miracle. The first poem of the section describes the miracle of a woman or girl having escaped a “boogeyman,” poses the giant question of how she did it, describing all of the obstacles in her way–everything from her school teacher to her pastor, right down to “the god of Abraham for not thinking about daughters.” In spite of all of this, Gumbs describes how “the inherited swiftness in her legs..let her run home that day,” allowing her to escape the boogeyman. In spite of a world which tries to destroy black life, strength, resistance, and fugitivity exist as a tradition, an inherited tool, and a constant. In fact Gumbs summed up her entire book when I saw her speak as “scenes of black women getting free from slavery until present.”

When I first picked up the book, I didn’t have any real sense of what “fugitivity” meant in Gumbs’ context, but as I heard her speak and describe her poetry in an interview with Jessica Marie Johnson in Black Perspectives, I came to understand it as a vehicle for resistance and liberation. Gumbs alludes to fugitivity both literally and with a broader sense of the definition. In the Black Perspectives interview, Gumbs describes referencing Harriet Tubman directly within the idea of fugitivity because “there is no understanding fugitivity without citing Tubman…” but also because “The thing that Harriet Tubman taught us about fugitivity was that being one person is not particularly strategic under the circumstances.” In calling out fugitivity as salient form of resistance during Antebellum slavery, she creates it as a thread through the history of black women right up to the present day. At the same time, Gumbs reminds us that fugitivity can look any number of ways–each poem, while each is a scene of fugitivity, is infinitely different from the last. Just as we shouldn’t need a reminder that there is no monolithic black female experience, we shouldn’t require this reminder about different forms of resistance, different types of fugitivity, but we still seem to. And Gumbs does it in a way that leaves room for interpretation, personal connection, and variation.